George Washington never told a lie. Columbus discovered America. Newton watched an apple fall out of a tree and figured out gravity.

These are some classic examples of the lies our text books told us. Of course most teachers don’t still teach these “facts”, they use nonfiction, historical fiction, and “updated” textbooks to teach history, social studies, and science. Before I started learning more about children’s lit, I admit I blindly trusted the authors of the books I used. I didn’t really know how to decide which books were more authentic, accurate, or trustworthy than others. I’d use any book if I had heard of the author, thought the publisher seemed reliable from my experience with them (like National Geographic), or even if the cover just caught my eye.

How silly was I.

How do you decide if the information in a book is trustworthy? How do you decide if a book is good enough to teach your kids without having to worry about un-teaching its information later? And how can you get kids to think about what they read?

The first time the falsity in a book truly shocked me was in my nonfiction class last semester. We had just read the book Amos Fortune: Free Man by Elizabeth Yates. Amos Fortune is the 1951 Newbery Award winner and a book I had taught in my classroom. A book I taught as fact.

The story is supposedly the true biography of Amos Fortune, an African-American slave turned free man. The author, Elizabeth Yates, begins the story with the kidnapping of Amos, an African Prince, who is eventually sold in the slave trade. An Amish man purchases him and then sells him to a tanner. Fortune learns the trade of tanning and eventually buys his freedom. He frees his wife, and they move to New Hampshire where he acts as a beacon of light to his community.

I taught this book a couple of times when I was in New Hampshire, I think many NH teachers do. I taught it as fact. Why wouldn’t I? I found it in the nonfiction section.

Well, after I read this for class my professor asked us if we’d like to have our minds blown away now or later. We decided on now.

“Well” she said, “about 95% of this book is made up.”

She went on to explain that there isn’t any record of Fortune’s life before he moved to Jaffrey, NH. Yates apparently didn’t think she could make his story compelling enough with the information she had, so she just made up the rest of the man’s life.

And when you realize some of the things Yates made up about Amos’s life, like the following conversation between the tanner and his wife, you begin to think about how much politics influenced the book.

“What happened to him?” Ichabod Richardson asked.

“I don’t know,” his wife replied. “Amos looked at himself in that little mirror he brought me and at first his image seemed to delight him. Then it affected him strangely.”

“Perhaps he thought he was white until he saw himself in the mirror (Yates 63).”

Really? Did this woman really think Amos was so stupid that he didn’t know what color he was? Or did Yates have to make Fortune inferior to white people in order to publish a book with an African-American protagonist in 1951? How could I trust this book?

Mortified that I had taught this book as fact, I made it my mission to make sure every educator and librarian in New Hampshire new to shelve this book in the historical fiction section. I swore to never use it in the classroom again.

But then I took a few breaths, settled down, and realized, that I could use this book in the classroom. I could use it in a way that is far better and more beneficial to students than just having them learn some facts about history from a book. In fact, you can apply this lesson to any book.

You have to teach your kids to think. Do you have to give your students reading fluency tests, like DIBELs? The thing I hate about most of these tests are that they focus on reading fluency and not comprehension. If a kid can read 132 words per minute but doesn’t know what he read, he’s not doing very well. In order for kids to understand what they’re reading they have to think about it. Teaching reading comprehension is one of the most difficult things for teachers to do, but hopefully this lesson idea will help.

First, pick a book (any nonfiction or historical fiction book works best). For the sake of this blog, we’ll stick with Amos Fortune.

You should do the lesson by yourself before you do it with your students. As the teacher you should know all the books you teach like the back of your hand. When it comes to nonfiction, you also need to know as much about the subject as possible.

Day One:

Let the kids get acquainted with the book. Give them a few minutes to flip through it. Then have them write a list of everything they know about the subject . It’s okay if they don’t know anything about it and it’s okay if they write some things down that you know aren’t true.

Next tell them that they aren’t going to just read the book, but they’re going to judge it. They’re going to decide if and why they think the book gives accurate information or not. They’re going to love having the authority to judge something an adult created. Have them make predictions. What do they think about the books accuracy just by looking at it?

Day Two:

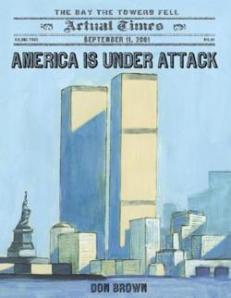

A: Show the students a few different books about the same subject. For example if your original book is about the Wright Brothers, then go to your library and grab at least five other books that are also about the Wright Brothers. Have the students spend a few minutes looking at each one and making notes about what they find. What does each book look like, is there an index, a bibliography, time lines, maps,a table of contents, diagrams, pictures, has it won awards, etc.? Have them decide which book (including the original book) they think is most trustworthy. Why do they think this? Leave these books on display for the next few weeks. Encourage the students to use them. If they come across an interesting fact in the book you’re reading ask them to see if the other authors included that information too. (Look at the pictures above… judge them. Which one do you think is most trustworthy? What about the cover made you make this judgement?)

B: If there aren’t any other books on the subject (like Amos Fortune) then try to find other sources of information. Use websites, pamphlets, articles, etc. Have them look over the information and decide what information they trust.

Day Three:

Ask the students to find the copyright date. Explain that world events can influence the production of a book. Discuss the events that were going on in the world during the books publishing date. Anything from political movements, to natural disasters, to popular trends can influence how and why a book is published (for example many books about Christopher Columbus were published in 1992 because it was the 500-year anniversary of Columbus sailing the ocean blue and in 2006, a year after Hurricane Katrina, there was an increase in information books about hurricanes).

Day Four:

Begin reading the book. I will eventually write a post about techniques to use during small reading groups. Just make sure your students are paying attention. Never have the students take turns reading a page or a paragraph or anything because the students won’t follow along, they’ll just wait until it’s their turn to read and daydream in the meantime. Have someone begin reading, when you think they’ve read enough call on somebody else. Do this randomly, even in the middle of sentences, this will keep them on guard and motivated to stay focused. Make sure there are consequences for when your students aren’t paying attention.

As the students read have them pay attention to how the author crafted the book. Does the author use quotations or invented dialogue? Is the author using references or do they seem to come up with their information out of thin air? Are there footnotes? Photographs? Illustrations? Diagrams? Author’s note? Make the children constantly question where the author is getting their information. Have them keep notes as they read for the next few days.

After Reading the Book:

Review what you’ve read. Discuss the book’s accuracy. Discuss the comparisons they made with the other books. Then have them decide whether they trusted the author. Would they read another book by them? Have them look at the original list they made of things they knew about the subject. Have them correct it and add to it. They’ll be surprised at how much they’ve learned.

As a final project have the students write a book review (allow them to use their books and notes). If they are able to make a decision about whether they trusted the information book and can defend their opinion then they have successfully learned a new comprehension technique. It’s perfectly ok if they don’t agree with your opinion about the book as long as they can defend themselves. Post their work up in the classroom. As a challenge have them pick another nonfiction book and write a report about why they think the author and information are reliable or not.

This activity should get your students (and maybe even you) thinking about books, especially nonfiction books, in a new way. Nonfiction is a world that adults always seem to tip-toe around. But students love nonfiction. Next time your students have some free reading time notice how many are reading the Guinness Book of World Records, or a book about sharks, skateboarding, ballet, or football. This activity is going to help them think about the books they already love!

Enjoy and happy reading!

(Grade level: k plus. This lesson can be modified for all ages)

Here is a list of nonfiction books I’ve read over the past year that I think are particularly exceptional:

**For anyone who is waiting for my response to the 2011 Caldecott awards, it will be up soon. I wasn’t expecting A Ball for Daisy to win and need some time to think about it! But congrats to all the winners! (Winner: A Ball for Daisy by Chris Raschka. Honors: Blackout by John Rocco, Grandpa Green by Lane Smith, and Me…Jane by Patrick McDonnell!)